The Iliad: Overview

HEROIC LITERATURE COURSE | Iliad overview

The Iliad is undoubtedly one of the most important and influential texts in all of literature. It is often called “the Bible of the Greeks,” but its influence continued long after the Christianization of Europe.

Although the Iliad is set during the Bronze Age, circa 1200 BC, it was composed and written down much later, around 800 BC, during the Archaic Period. Linguistic evidence indicates that it evolved over centuries as part of an oral tradition before it was eventually written down. The epic is composed in dactylic hexameter, the traditional meter of Greek epic poetry, ideal for memorization and oral performance.

The Iliad was part of the longer Greek Epic Cycle, which covered the events of the Trojan War from its cause and start, to the heroes’ homeward journeys and fates. Of these, only the Iliad and Odyssey, the only works in the Epic Cycle attributed to Homer, survive. I discussed this in greater detail in the Greco-Roman section overview.

To better understand the setting of the Iliad, we should first indulge in a brief overview of the history of the Ancient Greeks and the environment in which the Iliad was set and compose.

In the early Bronze Age, which began around 3,000 BC, Minoan civilization rose to prominence on the island of Crete. The Minoans were a sophisticated, seafaring people, with strong trade connections throughout the eastern Mediterranean. Genetically, they were primarily descended from the Neolithic Anatolian Farmers who occupied Europe before the coming of the Steppe peoples, with some additional genetic input from the Near East.

The Minoans wrote in a still undeciphered script (Linear A), so we know little of their beliefs or religious life other than the fact that bull iconography was prominent, as it was among the Anatolian Farmers and in the Near East.

Around 3,000 BC, the Indo-Europeans began to move into Europe, and from around 2000–1600 BC, they entered mainland Greece, bringing their language, religion, and values. They mixed with the local populations and gave rise to Mycenaean civilization c. 1600–1100 BC. These Mycenaeans, like the Minoans, took their ancestry primarily from the Anatolia Farmer populations of Europe, who had migrated from the Near East much earlier, mixing with Europe’s Western hunter Gatherer population. But the Mycenaeans now had an added 10-20% Steppe derived ancestry and had been heavily influenced by the gods, religion, language, social structure, and values of the Steppe peoples.

The myth of Theseus, an Athenian youth, overthrowing the Minotaur, the son of King Minos of Crete’s wife and a bull, likely reflects the Mycenean overthrow of Minoan civilization. King Minos is named after the Minoans, as is the Minotaur, who likely reflects their bull-worship, and the labyrinth on Crete may reflect a memory of the maze-like cities of Minoan civilization. After Theseus frees Athens from the yearly tribute of youths to the Minotaur, he renames the sea the Aegean, thus claiming symbolic control of the Mediterranean.

The Mycenaeans spoke Greek, an offshoot of the Indo-European language, and wrote using a script known as Linear B, adapted from the Minoans. Their society was built on palace-centered kingdoms on the Greek mainland, such as Mycenae, Argos, Pylos, Tiryns, Athens, Thebes, and what would later become Sparta. We have only palace records from this time, recording inventories of goods, animals, and people, but they indicate the existence of a warrior-aristocracy and a military elite.

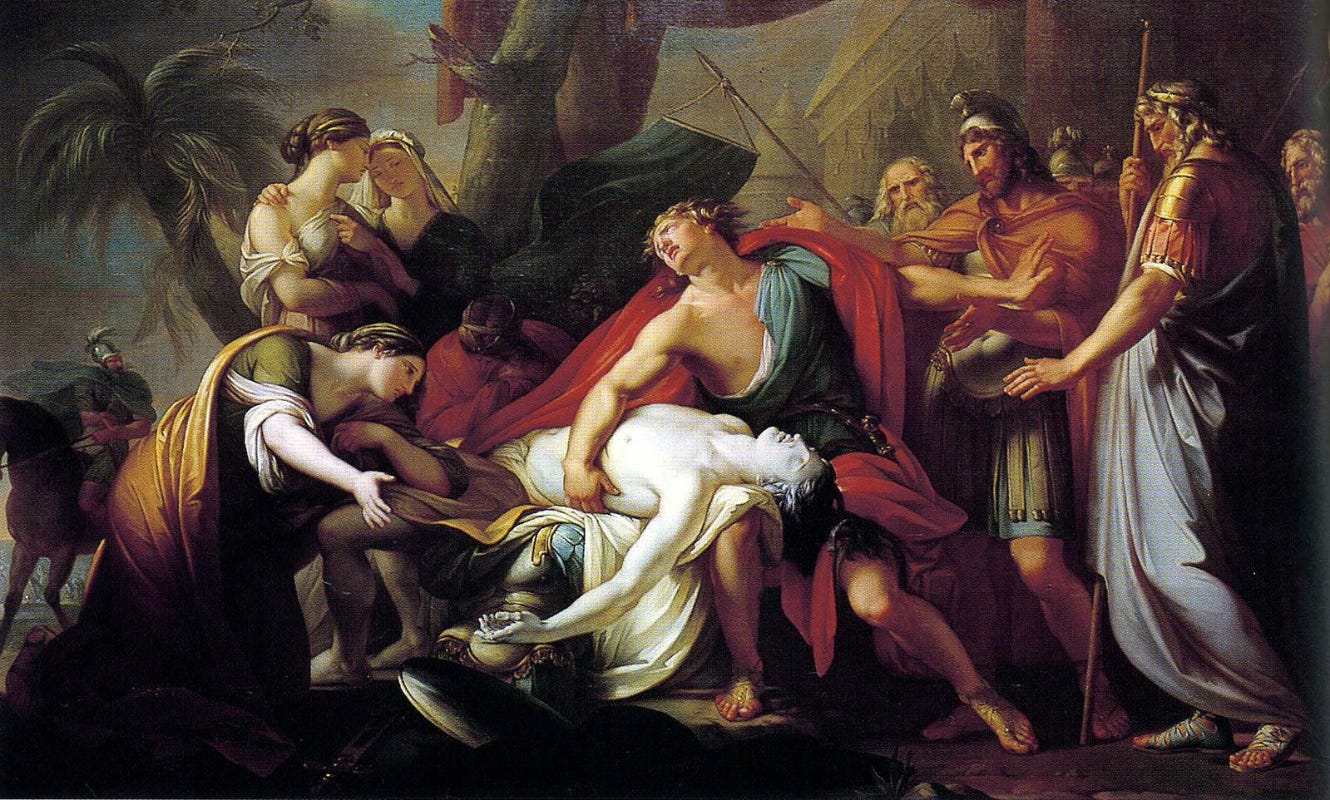

The Iliad is set during the Mycenean period. Agamemnon is the king of Mycenae, Menelaus of Sparta, Nestor of Pylos, Diomedes of Argos, Idomeneus of Crete, Odysseus of Ithaca, and so on. Homer refers to the Greek forces as Achaeans, Argives, and Danaans interchangeably, since there was not yet any idea of Hellenes or Greeks. The Trojan War, if it occurred would have happened circa 1,200 BC, near the end of the Bronze Age. And thanks to Heinrich Schliemann’s archaeological discoveries and records from the Hittite Empire, we know that the Iliad is indeed likely based on historical events and people.

At the age of just seven, Schliemann had declared that he was going to discover and excavate Troy. And later in his life, he would set out to do just that. He studied ancient texts, maps, and geographical descriptions to determine the most likely location for the city of Troy, settling on Hisarlik, a hill in modern-day Turkey, as his chosen excavation site. His efforts were met with skepticism from the academic establishment.

In March of 1871, Schliemann began his excavations and soon struck upon the ruins of a city, complete with fortifications, gates, walls, burnt debris and weaponry. Schliemann’s work led to the identification of nine distinct layers, each reflecting a different era of the city’s existence, stretching from settlements in the early Bronze Age to the Roman period.

Layer 6, circa 1700-1200 BC, was apparently destroyed by an earthquake, which may be reflected in the myth that Poseidon, god of the sea and earthquakes, built the walls of Troy with Apollo and that they sent plagues and a sea monster to ravage Troy when they were not paid. Layer 7, dated to c. 1200–1180 BC, showed signs of violent destruction and could correspond with the events of the Iliad, though it’s impossible to know for certain.

As Schliemann continued to excavate, he discovered a hoard of gold and silver artifacts which he referred to as Priam’s Treasure and included jewelry, vases, and a diadem which Schliemann dubbed the Jewels of Helen. This captured the imagination of the public and soon headlines read that Schliemann had discovered the lost city of Troy.

Schliemann would also conduct other digs in Greece, uncovering the funeral shafts at Mycenae and, in them, the golden funeral mask which he famously called the Mask of Agamemnon. It is unlikely to be related in any way to the Historical Agamemnon, if he existed, but is an impressive artifact nonetheless.

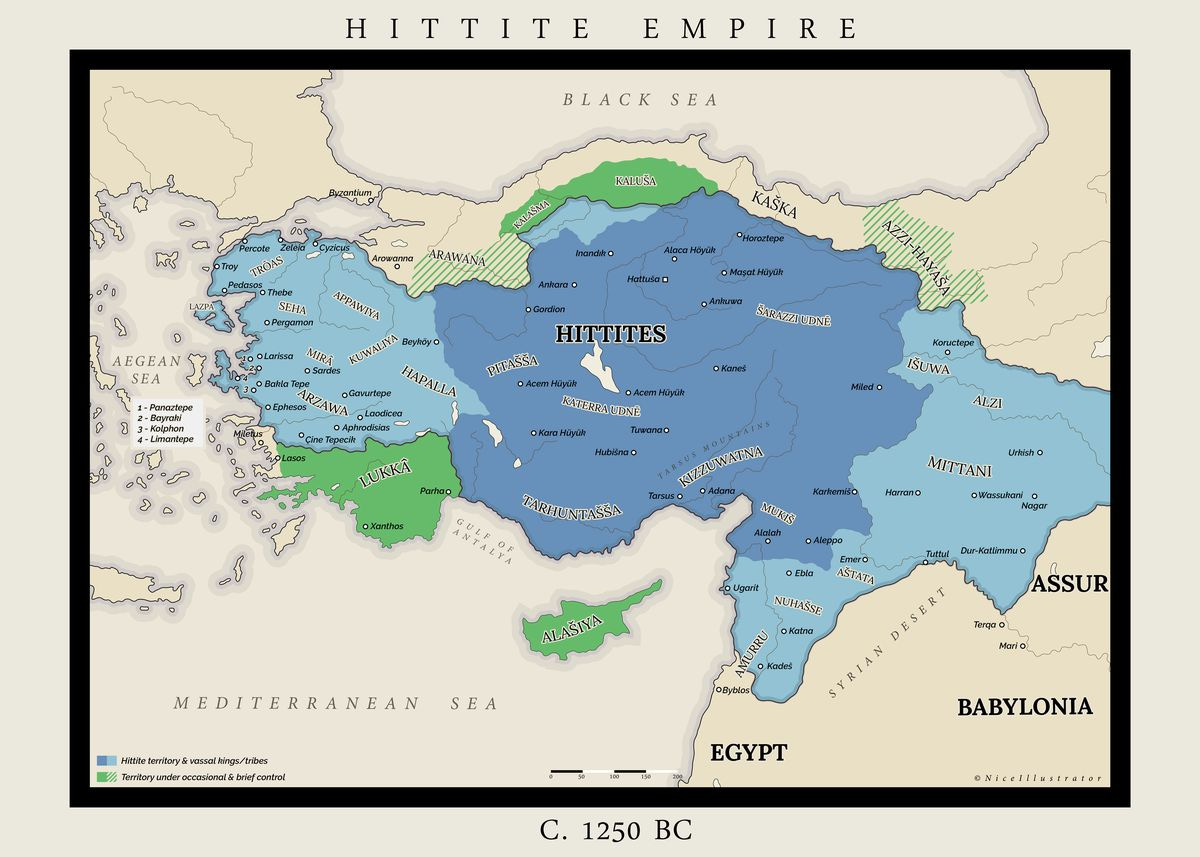

Beginning in the 1920s, Hittite records were translated which seem to provide further proof of the Iliad’s relative historicity. The Hittites were an ancient Anatolian people who established a powerful kingdom centered in modern-day Turkey during the Late Bronze Age.

The diplomatic correspondence known as the Ahhiyawa Letters contain references to various political and diplomatic exchanges between the Hittite Empire and the Ahhiyawan state. Linguists believe that Ahhiyawa is the Hittite word for the Achaeans. The letters discuss matters such as the release of prisoners, disputes over territory, and requests for military assistance. They also mention interactions with a land called Wilusa, which many scholars believe to be an Anatolian rendering of Ilion or Ilios, the ancient name for Troy from which the name of Homer’s Iliad is derived.

One of the most intriguing Hittite records is the Tawagalawa Letter, which contains a reference to a figure named Tawagalawa, who has been linked by some scholars to the Greek figure Eteocles, son of Oedipus, since his name appears in the earlier form Etewoklewes.

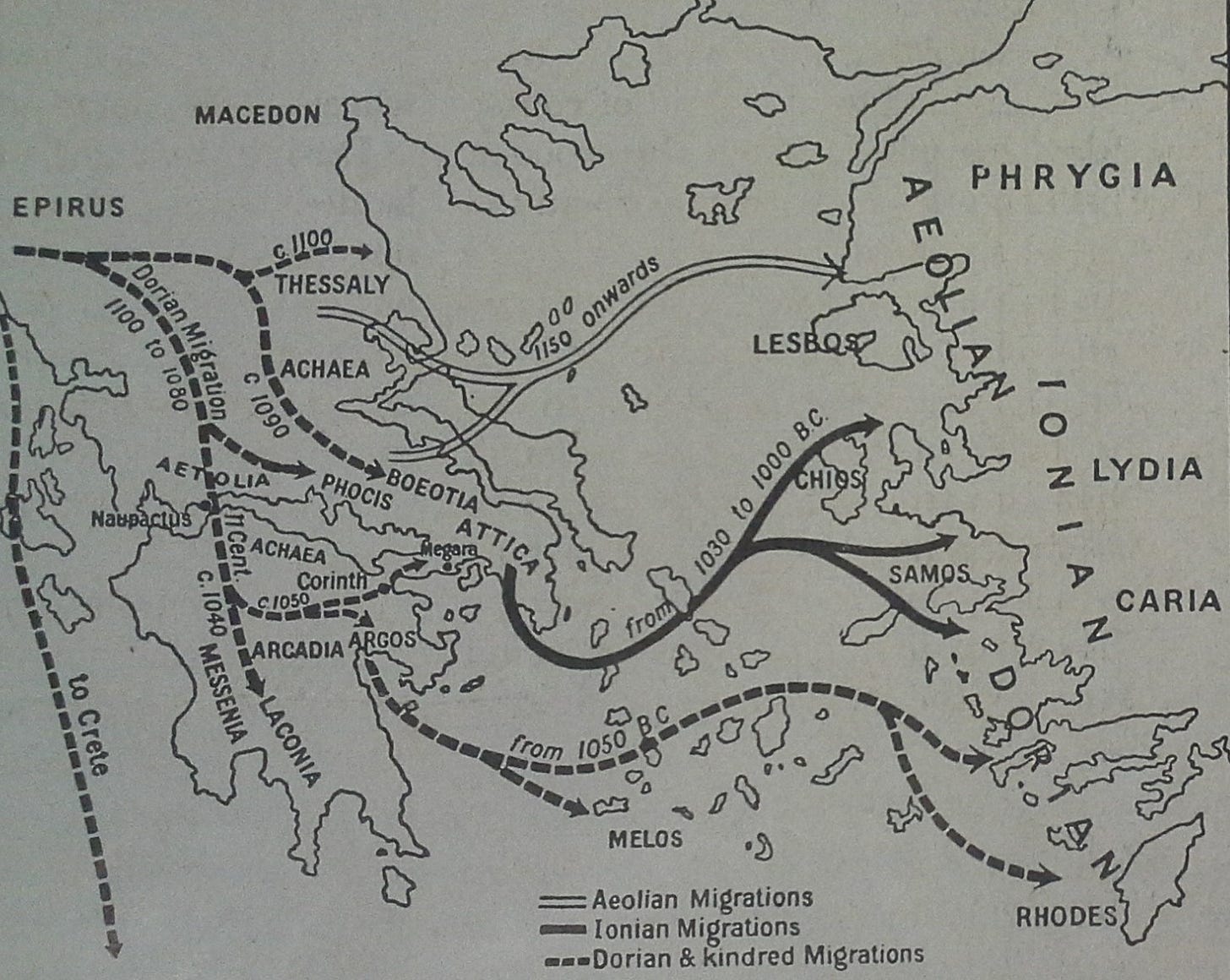

Mycenaean civilization began to collapse in around 1200 BCE when the entire Mediterranean and Near east was struck by what is called the Bronze Age Collapse. In Greece, the Mycenaean palaces were burned and abandoned, Linear B writing disappeared, trade routes dissolved, and the population declined sharply. The cause of this large-scale collapse of the Bronze Age world remain debated.

What followed was the Greek Dark Age, lasting from c. 1100–800 BCE. Literacy vanished and the social structure became far less centralized. During this time the Greek-speaking Dorians, the ancestors of the Spartans who claimed descent from Herakles, moved down into Greece, settling in Sparta and across the Peloponnese. The Greek Ionians also moved east, colonizing the coast of Asia Minor.

It is at the end of the Greek Dark Age, circa 700-800 BC, that the Iliad and Odyssey were composed, doubtless based on much older oral legend. During this time, writing returned, but now using our alphabet, borrowed from the Phoenicians. In the following Archaic period, c. 800–500 BC, the city-state emerged and Greek civilization began to flourish again. In 776, the first Olympic Games were held. The Iliad, therefore, remembers the grandeur and tragic collapse of the Bronze Age aristocracy, while also laying the cultural foundations of the Greek Classical Age.

As the Persians came to power in Asia Minor, conquering the coastal Greek colonies, tensions arose between the Greeks and the Persians which culminated in the Ionian revolt of 499 BC. In response, the Persians launched two invasions of Greece, first under Darius and then under his son Xerxes. Both were repelled, and Greece entered the Classical Age, marked by the flourishing of Greek tragedy, largely based in the same mythic material as the Iliad and Odyssey, which would likely have felt all the more relevant after an invasion from Asia Minor. Veterans of the Greco-Persian Wars would have related deeply to the Iliad and would have seen hostilities on the coast of Asia Minor as a reflection of the age old feud which began with Helen.

From 431-404 BC, The Peloponnesian War between Athens and Sparta broke out. The war concluded with Spartan victory and the collapse of Athenian domination in the Mediterranean, leaving the Hellenic world vulnerable. In 334 BC, Alexander, king of Macedon, began his conquest of Greece, launching the Hellenistic Age. From 214 to 142, the Roman Republic engaged in a conquest of Greece, but the Hellenic Age continued in Egypt and Asia Minor until the birth of the Roman Empire when Augustus defeated Mark Antony and Cleopatra, taking control of Egypt. We will pick up the thread of Roman history when we come to the Aeneid.

NARRATIVE BACKGROUND

Here is an overview of what we know from summaries and fragments about the plot of the entire Greek Epic Cycle. I tried to keep it as concise as possible.