Nietzsche is often characterized by the public as the "edgy atheist philosopher” or the “anti-Christian philosopher,” but his Pagan influence is almost entirely ignored. Much of Nietzsche's philosophy grew out of his investigation of the values of the European pagans, who he characterized as healthy, vital, and life-affirming. He repeatedly called himself a disciple of Dionysus and said that in the secret of the Dionysian Mysteries, in the idea that immortality is found in the continual intergenerational rebirth of biological life rather than the immortal soul, he had found the path to a truly life-affirming worldview.

“I know of no higher symbolism than this Greek symbolism, this symbolism of the Dionysian phenomenon. In it, the profoundest instinct of life, the instinct that guarantees the future of life and life eternal, is understood religiously—the road to life itself, procreation, is pronounced holy.”

Twilight of The Idols

In Will to Power, Nietzsche even refers to himself as a pagan, saying, “We few or many who again dare to live in a dismoralized world, we pagans in faith: we are probably also the first to grasp what a pagan faith is:—to have to imagine higher creatures than man, but beyond good and evil; to have to consider all being higher as also being immoral.”

But I will not argue that Nietzsche himself was a Pagan in any religious sense, or that all of his philosophy agrees with the European Pagan worldview. Nietzsche was his own man with his own novel philosophy. Instead, I hope to show that, in his idea of the will to power, Nietzsche articulated the fundamental metaphysical principle which is the foundation of the European Pagan worldview—that is, the religious and moral worldview held in common across Europe before Christianity and before Platonism and various other philosophies began to dominate the classical world. This is the worldview which we see exemplified in Homer, in the Norse sagas, in Irish heroic literature, and even Arthurian Romance.

So, what exactly is the “will to power?” People often assume that Nietzsche is making the claim that everyone is simply motivated by the cold desire for power—political power or power over others—which is not the case at all. Nietzsche does make the claim that people tend to hold worldviews and values which facilitate their flourishing, and in that way are self-serving, but this is only common sense. And it is only a downstream from Nietzsche's much more profound idea of the will to power as the driving force—the fundamental essence of biological life. The will to power is not meant to describe a singular desire, power, which people seek after and prioritize over love or any number of other things. Instead, it is meant to describe the nature of biological life.

And what do we mean by nature? A brief digression into etymology is needed:

Nature, late 13th century., "restorative powers of the body, bodily processes; powers of growth;" from Old French nature, “being, principle of life; character, essence," from Latin natura "course of things; natural character, constitution, quality; the universe," literally "birth," from natus "born," past participle of nasci "to be born" (from PIE root *gene- "give birth, beget").

By the mid 14th century, "the forces or processes of the material world; that which produces living things and maintains order." From late 14th century onward as "creation, the universe, natural world;" also "heredity, birth, hereditary circumstance; essential qualities, inherent constitution, innate disposition" (as in human nature).

When we refer to someone's "nature," we are referring to their fundamental, essential characteristics—the tendencies of behavior which they were born with. We can also refer more generally to “human nature”—that is, the nature, the essential qualities, the essential modes of behavior common to all of mankind. But it doesn't stop there. We can keep getting broader. All mammals share a similar nature. This is why we can relate well to dogs, monkeys, and even cats, and establish a mutual understanding with them, while the same would be impossible with a scorpion or beetle. We can easily recognize how mammals are feeling and communicate with them across species through shared modes of behavior and expressions of emotion and desire. In the wolf, we recognize ourselves, while in the snake, we see only a cold, heartless predator.

So, what happens when we ask, “what nature is common to all living organisms?” Is there some essential essence or mode of behavior which all living organisms share? Nietzsche's answer is yes, and he calls it the will to power. All living organisms seek expansion, growth, the fulfillment of their organism's potential, and the mastery of their environment. The tree stretches its branches up towards the light, growing taller and taller, consuming as many nutrients as it can, often to the detriment of other trees and plants, since resources are limited. And it is the same with people. People consume nutrients, often in the form of other animals, and it is turned into muscle and bone tissue. As we mature, we grow stronger and taller. We seek to exercise our strength and master our environment. We can see that all organisms, no matter how small, are governed by this same essential drive—by this same process of consumption and growth. In fact, we might say that every organism is, fundamentally, the will to power expressed through a specific, limited structure. Only the limited potential of individual organisms, and the pull of entropy, restrict life’s relentless thirst for expansion and growth.

So, we can see that the idea of the will to power is a fundamentally biological idea. It is not describing some cold Machiavellian drive to power which we all harbor and conceal in our hearts, nor is it reductionistic and mechanistic. This will to power can be expressed in any number of ways, and is at the root of all instincts and behaviors. It is expressed through reproduction, by which life bypasses death, and through competition, as organisms seek out resources and territory, but it can also be expressed through laughter, through dancing, through art, and through play.

We become depressed when we are confined, imprisoned, unable to explore and master our environment, unable to express our abilities, our powers, unable to discharge the energy of our instincts, unable to express the full potential of our being and to test our abilities against the world, because our deepest, most fundamental instinct is the drive towards growth, towards expansion, towards mastery. All instincts, all behaviors, no matter how purposeless and trivial, all human values, are an extension of this fundamental nature. Life does not seek to merely survive.

Now let's turn to the European Pagan worldview. To keep things simple, I'm going to stick to four essential ideas which were central to the European Pagan worldview and are all interconnected: the idea of excellence or heroism, the idea of custom or virtue, the idea of nature, and the idea of fate. We can tell that these ideas were central to the European Pagan worldview because we see them in both the Norse sagas, which were written down around 1000 AD, and in Homer, which was written down around 800 BC. The Greek and the Norse texts, which, among others, preserve for us the European Pagan worldview, were both geographically and temporally distant, and yet we see in them the exact same ideas about heroism, fate, nature, and custom.

So, firstly, what exactly is a hero? The hero, whether Achilles or Sigurd, is a man of high birth who seeks and achieves excellence, who performs great feats and overcomes great obstacles, and who exhibits all the markers of flourishing life—beauty, physical strength, and mental sharpness. So we could say that a hero is essentially someone who possesses a heightened “will to power,” or more colloquially, a stronger “life force.” Their drive towards excellence—that is, their biological will to power—is stronger than others, and the actual potential of their body and spirit, of their physical organism, is greater than others’. And for this reason, they excel over their peers. They are the tallest tree in the forest of great men.

For the Pagan cultures of Europe, it was all of the markers and the fruits of a natural, organic excellence which were considered good—both physical qualities like beauty and strength, and virtues like boldness and grace. They valued the markers of healthy, flourishing life, and the underlying nature which those markers—excellence of body, spirit, and deed—revealed. However, this does not mean that they adhered to some kind of Darwinian, "might makes right" ideology. They had sacred morals, laws, and codes of custom.

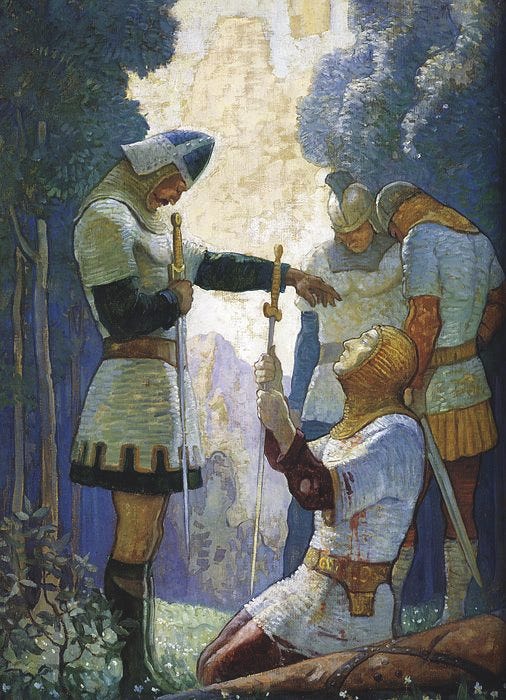

In The Iliad and The Odyssey, Zeus is called “the god of the suppliant,” and will punish those who violate the rights of the suppliant. If you abused your guest, your host, or a suppliant, if you violated custom or law, there would be consequences. This ethical code survived even into the Arthurian Romances of the late Middle Ages, where one is obliged to offer servitude instead of death if a defeated knight—one who has not committed too severe of an offense—supplicates himself and asks for mercy.

However, for the Pagans, there was no illusion that these laws were a part of nature. Laws exist only for men, albeit enforced by the gods. This is what Achilles means when Hector asks for a proper burial in accordance with custom, and Achilles replies, "There are no pacts between lions and men, and there can be no peace between wolves and sheep." In response to Hector’s appeal to custom, Achilles asserts that there are no laws in nature. The natural world is a free-for-all, the amoral struggle of all against all, and there are no guarantees of cooperation or mercy. Laws are imposed upon nature to facilitate cooperation, just as the hero imposes virtue on himself to direct his raw nature towards excellence. But this does not in any way diminish the sanctity of custom and law.

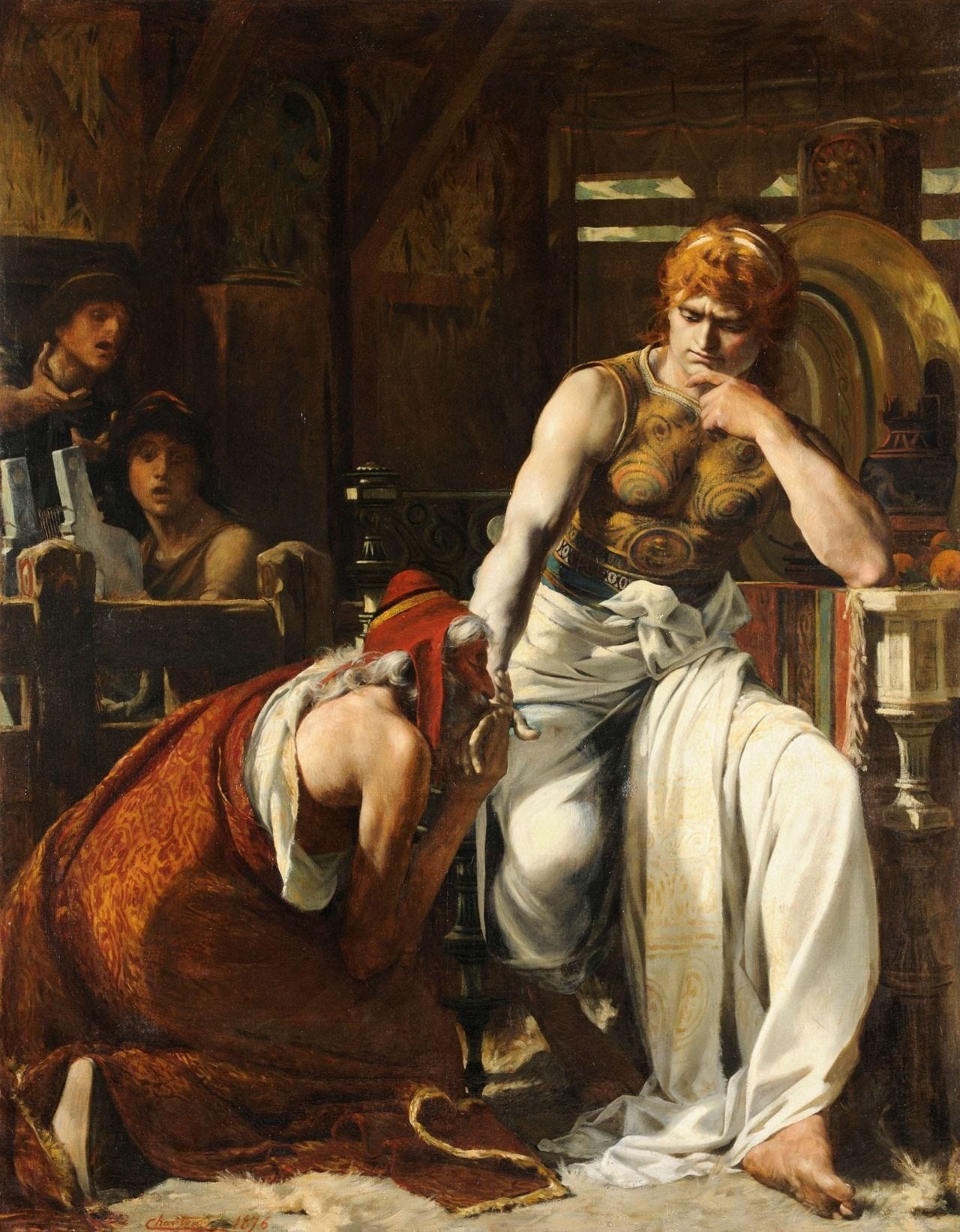

In the Iliad, the central drama of the epic begins because Agamemnon takes Achilles’ beloved concubine, Briseis, violating custom. As a king, it is his obligation to be generous with his wealth, to reward his men with gifts and prizes, to nourish his people, but instead, he becomes a “king who devours his own people,” as Achilles calls him (Robert Fagles translation). This leads to a series of violations of custom. Agamemnon offers Achilles great compensation and the return of Briseis, which Achilles refuses in violation of custom—“compensation” was an important custom seen in both the Greek and Norse texts which prevented endless revenge killings—Achilles refuses to grant Priam’s defenseless son, Lycaon, mercy, and refuses to grant Hector a proper burial. But in the end, even the unyielding Achilles gives way to custom when Priam comes to his tent as a suppliant. Achilles returns Hector’s body to his father, saying, “…don’t anger me now, don’t stir my raging heart still more, or under my own roof, I may not spare your life old man, suppliant that you are, I may break the laws of Zeus.” Ultimately, Achilles submits his proud nature to custom.

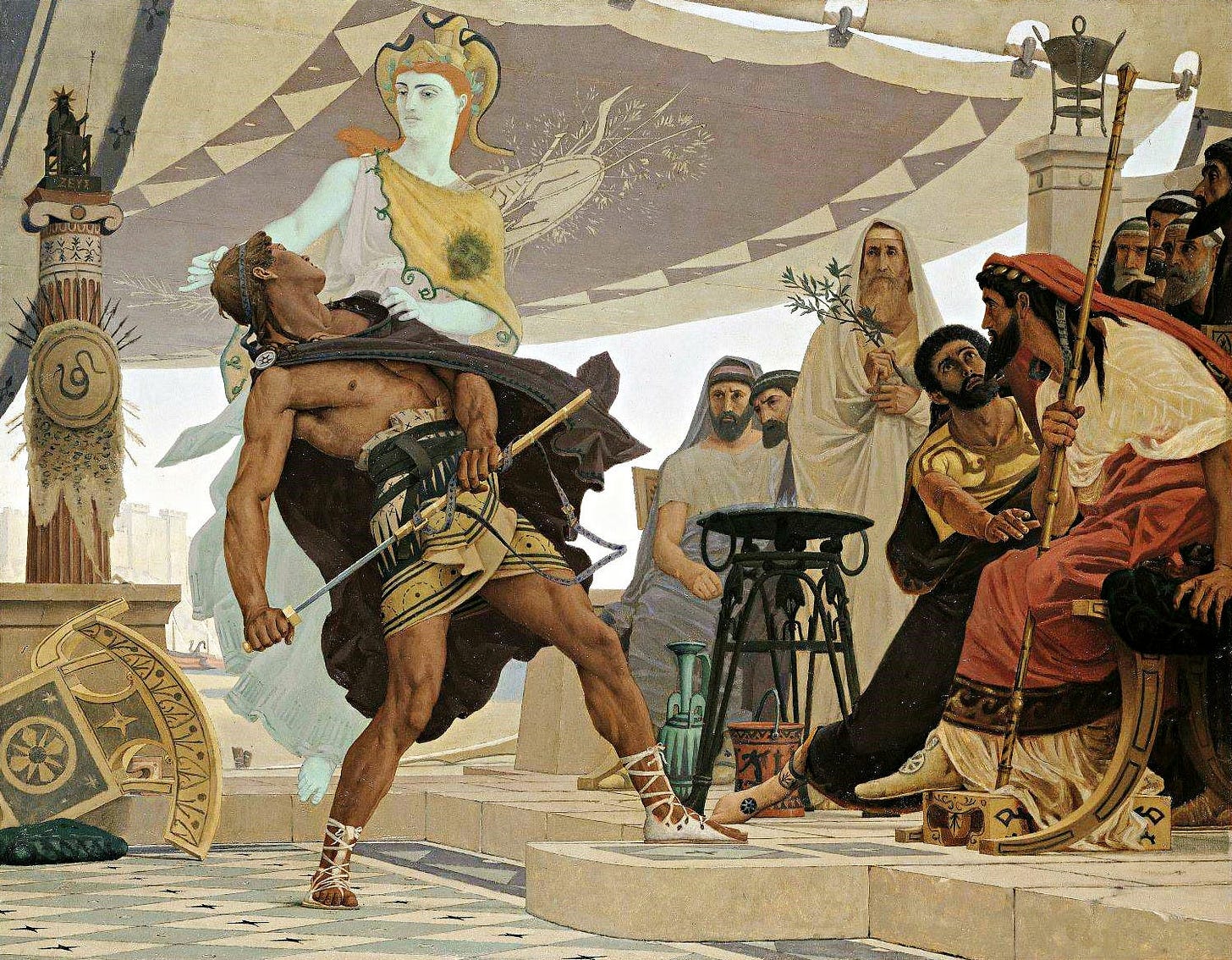

Similarly, in the Odyssey, the plot revolves around a series of violations of hospitality customs—the Cyclops, who devours his guests, Calypso and Circe, who imprison their guests, and most importantly the suitors, who devour the wealth of their own king. The Odyssey concludes with divine justice, as the suitors are slaughtered by Odysseus, with the help of Athena, for their violation of custom, and Athena remains among them in the guise of the hero Mentor to maintain peace.

And this brings us to the idea of fate, which Nietzsche flirted with when he wrote against the existence of free will. In the European Pagan view, everyone is bound by a fate which they cannot escape, and this fate is tied to one’s nature. In The Saga of the Volsungs, when Volsung is warned about an impending ambush, he says that he swore an oath in the womb to never flee from iron or fire. He cannot flee because his nature will not allow him to. And in Greek mythology, we see that certain fates, certain tendencies of behavior, can be tied to a specific bloodline and passed from generation to generation, as is the case with the curse of the House of Atreus.

Achilles is a great illustration of this principle. Zeus lusted after Achilles’ mother, Thetis, but upon learning that her son was prophesied to surpass his father, Zeus married her off to a mortal, fearing that he would be overthrown as he had overthrown his father, and his father had overthrown his grandfather before him. And in Achilles conflict with Agamemnon— “a king who devours his people,” much like Kronos—we see that Achilles would indeed have rebelled against his father Zeus, had he been his son, since it is in his nature to rebel against authority. And it is precisely Achilles’ rebellious and proud personality which stokes the flames of his conflict with Agamemnon, leading to Patroclus’ death and sealing his own fate.

Thus, we can see that fate is tied to and follows from one’s nature. Just as species are bound to a certain range of behaviors tied to their nature—a dog cannot stand up on its hind legs and start speaking—individuals can only exhibit a certain spectrum of behavior, and that nature determines how they live their life and what fate they eventually meet.

Now, back to the will to power as the foundational metaphysic of the European Pagan worldview. By “metaphysic,” I mean to say the fundamental presupposition about the nature of the world upon which the entirety of a worldview, its view of reality and morality, rests.

The fundamental metaphysical idea behind Christianity, for example, is that the world began in a perfect state without death, that we are fallen into a world of sin and death, and that we can be restored to our original state of perfection and immortality through Christ. If this is not the case, then all of the rest of Christian theology and morality crumbles.

And I think that in his idea of biological life as the will to power, and the world more generally as the will to power (we didn't have time to get into that here), Nietzsche was the first to articulate the metaphysical principle underlying the European Pagan worldview in philosophical terms.

If you're interested in learning more about the European Pagan worldview, I have an ongoing Heroic Literature course here on Substack, in the form of 30-50 minute audio episodes. When it’s complete, we will have covered the Greco-Roman epics, the Norse sagas, Irish heroic literature, and finally Arthurian Romance, tracing the evolution of the heroic worldview from 800 BC to 1400 AD. I'm essentially trying to give you the value of a college course, but more interesting, more convenient, and a lot cheaper. So, check it out if you're interested.

Fun read.

Enjoyed this.